IN AN ORDINARY hospital room in Los Angeles, a young woman named Lauren Dickerson waits for her chance to make history.

She’s 25 years old, a teacher’s assistant in a middle school, with warm eyes and computer cables emerging like futuristic dreadlocks from the bandages wrapped around her head. Three days earlier, a neurosurgeon drilled 11 holes through her skull, slid 11 wires the size of spaghetti into her brain, and connected the wires to a bank of computers. Now she’s caged in by bed rails, with plastic tubes snaking up her arm and medical monitors tracking her vital signs. She tries not to move.

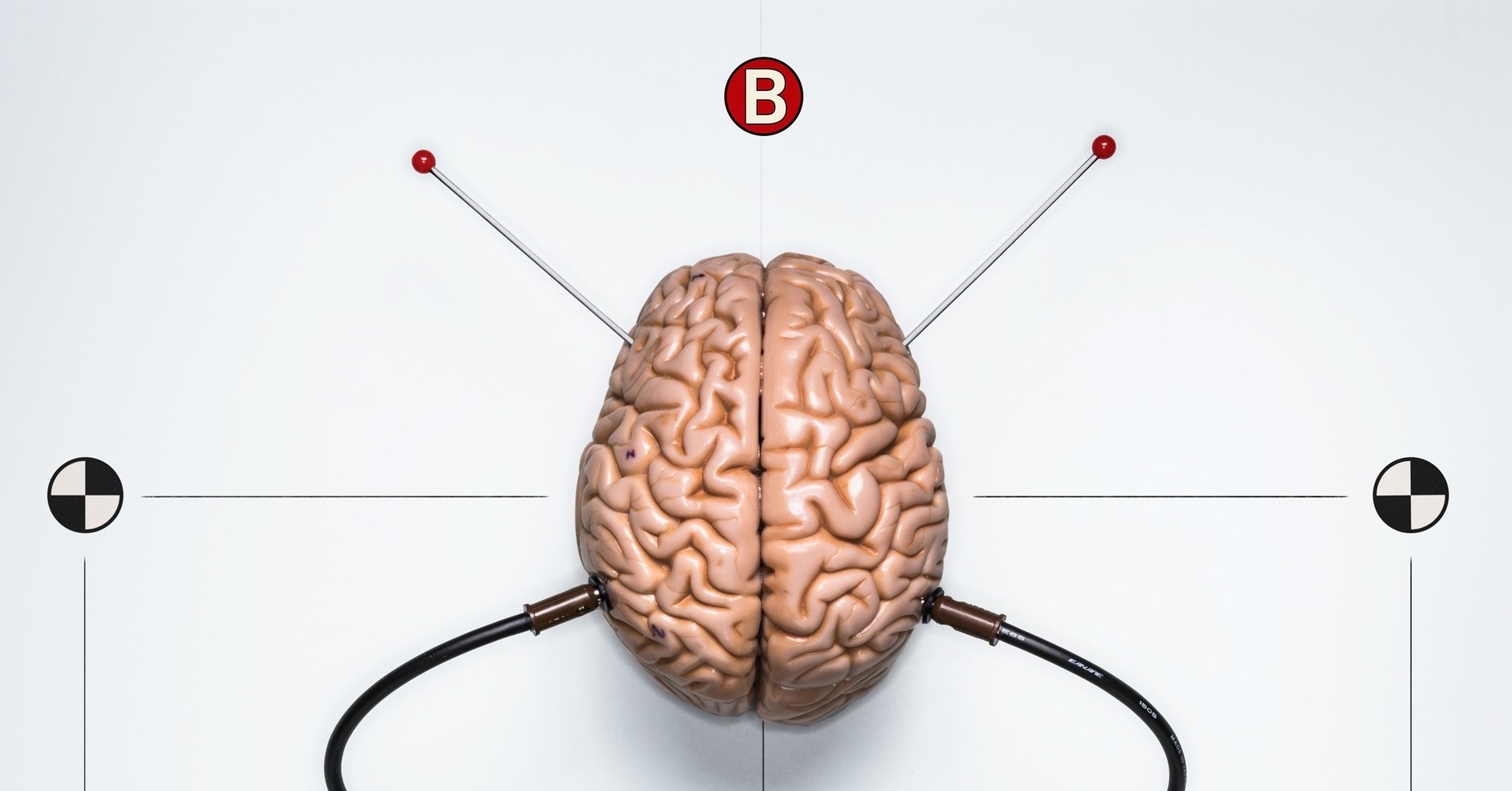

The room is packed. As a film crew prepares to document the day’s events, two separate teams of specialists get ready to work—medical experts from an elite neuroscience center at the University of Southern California and scientists from a technology company called Kernel. The medical team is looking for a way to treat Dickerson’s seizures, which an elaborate regimen of epilepsy drugs controlled well enough until last year, when their effects began to dull. They’re going to use the wires to search Dickerson’s brain for the source of her seizures. The scientists from Kernel are there for a different reason: They work for Bryan Johnson, a 40-year-old tech entrepreneur who sold his business for $800 million and decided to pursue an insanely ambitious dream—he wants to take control of evolution and create a better human. He intends to do this by building a “neuroprosthesis,” a device that will allow us to learn faster, remember more, “coevolve” with artificial intelligence, unlock the secrets of telepathy, and maybe even connect into group minds. He’d also like to find a way to download skills such as martial arts, Matrix-style. And he wants to sell this invention at mass-market prices so it’s not an elite product for the rich.

Right now all he has is an algorithm on a hard drive. When he describes the neuroprosthesis to reporters and conference audiences, he often uses the media-friendly expression “a chip in the brain,” but he knows he’ll never sell a mass-market product that depends on drilling holes in people’s skulls. Instead, the algorithm will eventually connect to the brain through some variation of noninvasive interfaces being developed by scientists around the world, from tiny sensors that could be injected into the brain to genetically engineered neurons that can exchange data wirelessly with a hatlike receiver. All of these proposed interfaces are either pipe dreams or years in the future, so in the meantime he’s using the wires attached to Dickerson’s hippocampus to focus on an even bigger challenge: what you say to the brain once you’re connected to it.

That’s what the algorithm does. The wires embedded in Dickerson’s head will record the electrical signals that Dickerson’s neurons send to one another during a series of simple memory tests. The signals will then be uploaded onto a hard drive, where the algorithm will translate them into a digital code that can be analyzed and enhanced—or rewritten—with the goal of improving her memory. The algorithm will then translate the code back into electrical signals to be sent up into the brain. If it helps her spark a few images from the memories she was having when the data was gathered, the researchers will know the algorithm is working. Then they’ll try to do the same thing with memories that take place over a period of time, something nobody’s ever done before. If those two tests work, they’ll be on their way to deciphering the patterns and processes that create memories.

Although other scientists are using similar techniques on simpler problems, Johnson is the only person trying to make a commercial neurological product that would enhance memory. In a few minutes, he’s going to conduct his first human test. For a commercial memory prosthesis, it will be the first human test. “It’s a historic day,” Johnson says. “I’m insanely excited about it.”

For the record, just in case this improbable experiment actually works, the date is January 30, 2017.

Sourced through Scoop.it from: www.wired.com

Leave A Comment