Thompson says Uber’s system for paying drivers—offering lower rates per ride but bonuses for hitting specified targets—deters part-time drivers. He says Uber’s need to reform this system is similar to Khosrowshahi’s experience transitioning Expedia’s business model.

A bigger problem in the short term, says David Yoffie, a professor at Harvard Business School, is the need to fill out Uber’s executive ranks. Kalanick is among more than a dozen executives to leave their jobs this year, including president Jeff Jones, head of finance Gautam Gupta, and senior vice president of engineering Amit Singhal. “You can’t run a company by committee which is how they’ve been run for three months now,” Yoffie says.

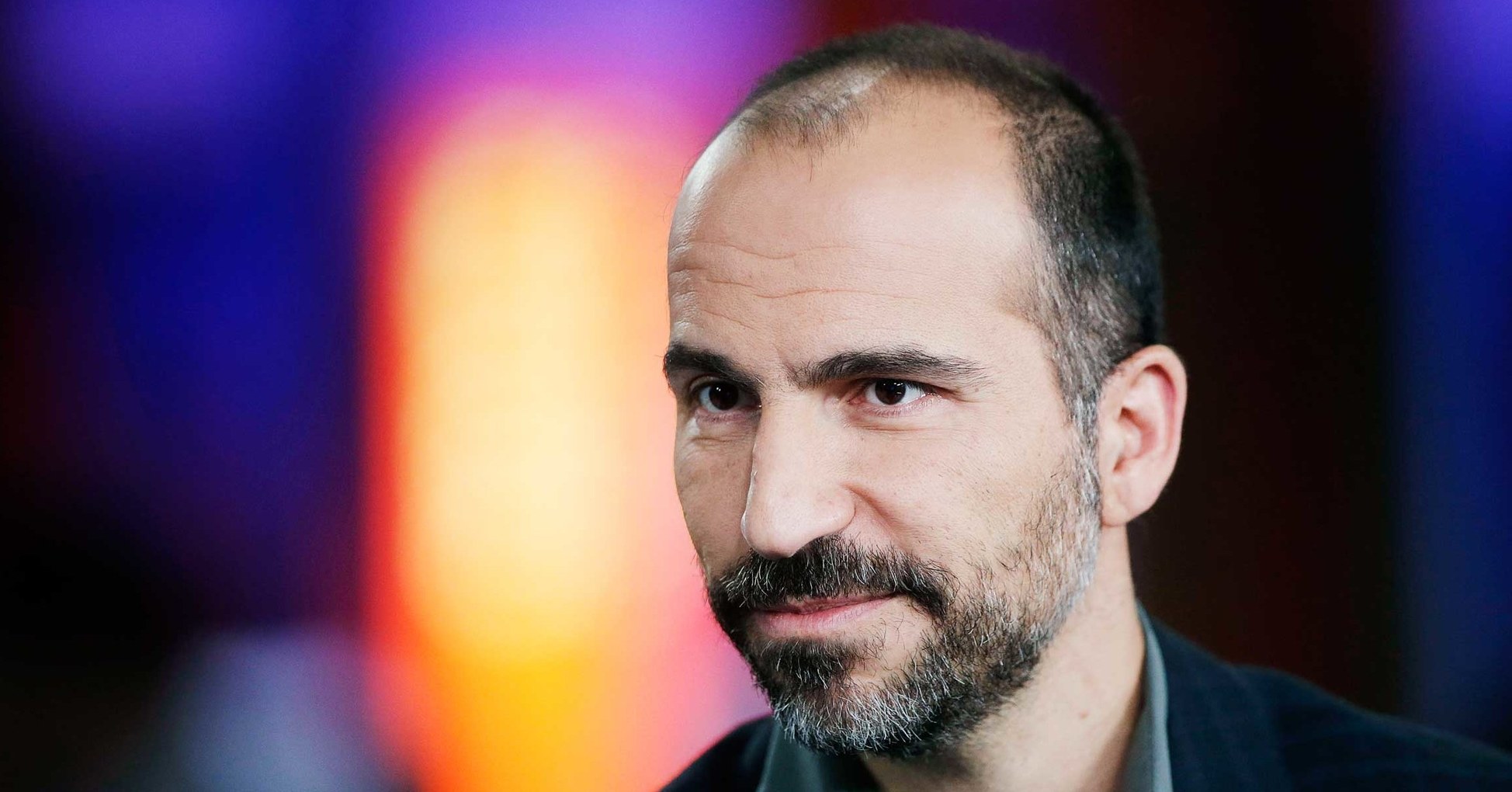

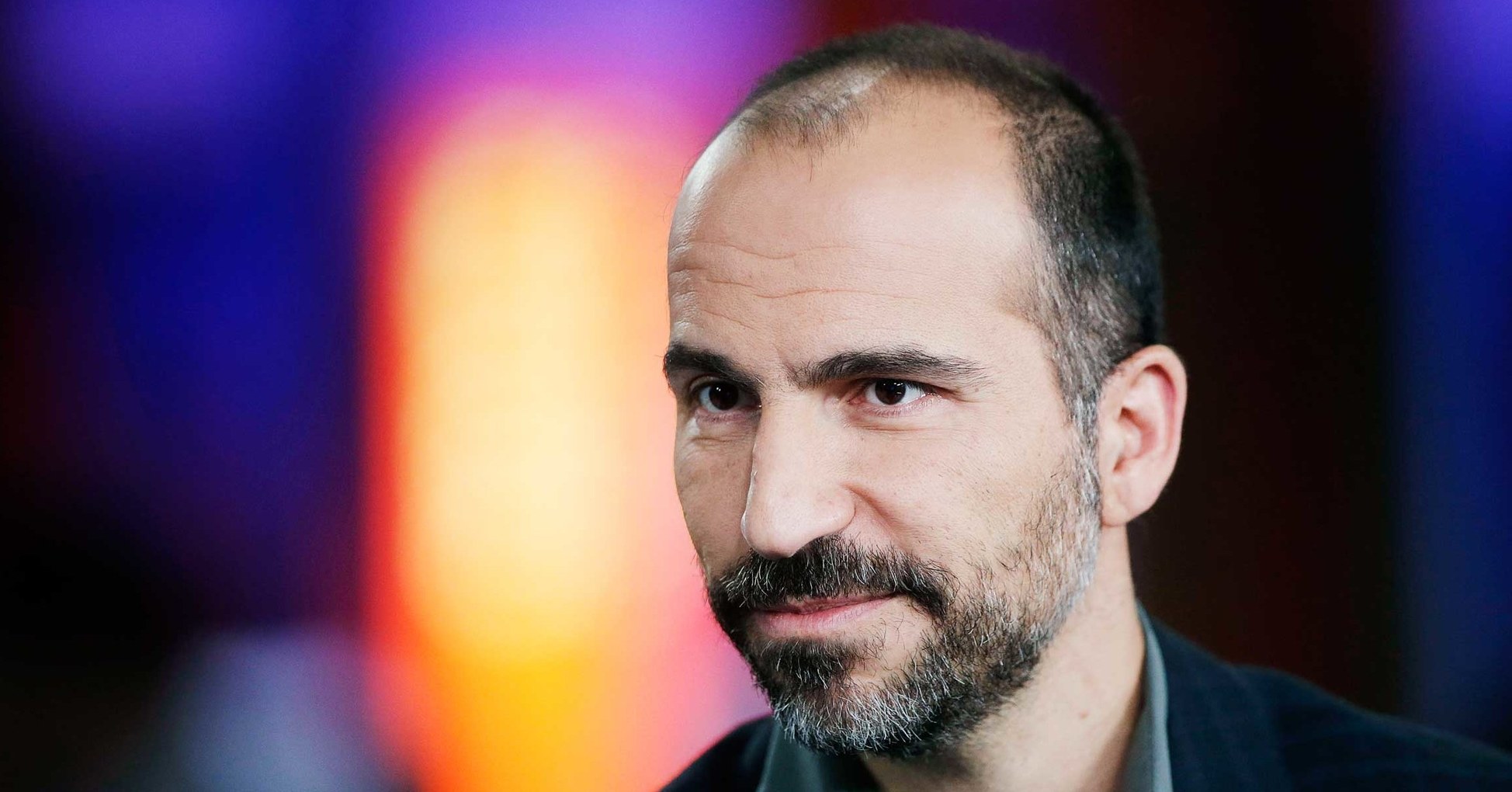

Khosrowshahi may be well positioned to solve this problem. Although he’s is based in Bellevue, Washington, where Expedia is headquartered, Khosrowshahi has significant ties to Silicon Valley and “one of the most extensive family networks of anyone working in the technology industry today,” says the Washington Post. His brother, Kaveh Khosrowshahi is managing director of Allen & Co., and his twin cousins, Ali and Hadi Partovi, are early investors in Uber, Airbnb, Dropbox, and Facebook, and cofounded the nonprofit Code.org.

Reforming the top level of management would also be the first step towards reforming the company’s corporate culture, which is at the root of its many scandals. But Levick says Khosrowshahi should also make efforts to attract more a more diverse talent pool through aggressive–and highly visible–recruiting programs. “Uber needs to become synonymous with opportunity, not misogyny,” he says.

Khosrowshahi may have one other thing going for him: The many people who have never used, or heard of, ride-hailing. A survey by Pew Research published last year found that only 15 percent of respondents in the US had used a ride hailing app like Uber or Lyft, and about one-third percent of respondents had not heard of either company.

Sourced through Scoop.it from: www.wired.com

Leave A Comment